While the virus is resulting in the tragic loss of life, we must nonetheless prevent it from destroying our way of life — our understanding of who we are, what we value, and the rights to which every European is entitled.

— Marija Pejčinović Burić, Secretary General of the Council of Europe at the Saint Petersburg International Legal Forum

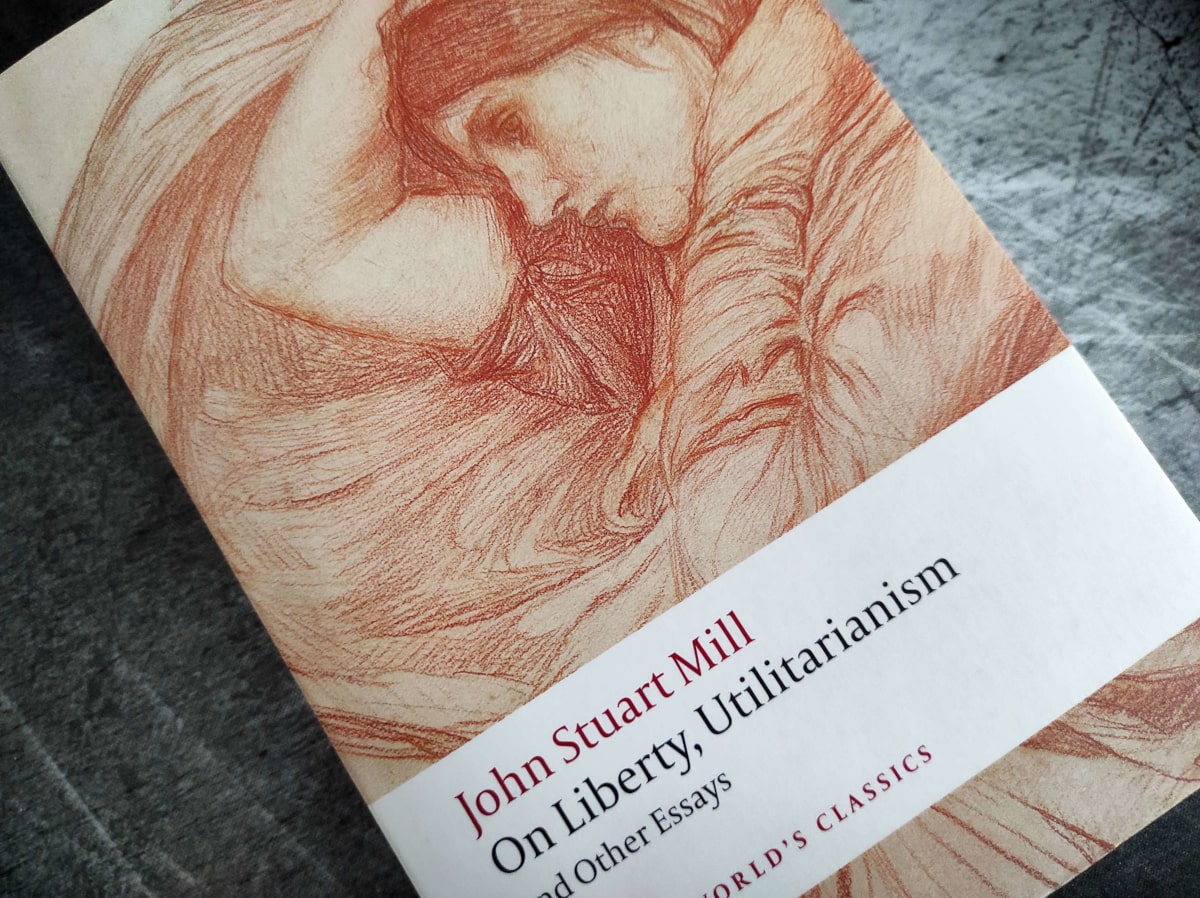

The struggle to find the line that separates the individuals’ liberties and government authority that dominates many debates surrounding the current pandemic was actually framed 169 years ago by John Stuart Mill, an English philosopher that together with Jeremy Bentham is considered one of the fathers of utilitarianism.

In 1859, Mill published an essay titled On Liberty in which he studies the relationship between government and the people: the liberties of the individual versus the authority of society to interfere. Where is the limit “between individual independence and social control”, Mill asks.

In the following, I will summarise a few relevant concepts of his argument and provide the links with today’s situation. If you have the time, I suggest you read the essay as much more than I can relay here is still incredibly apt.

The tyranny of the majority

To start his reasoning, Mill recognises the dangers of the tyranny of the majority. He recognises that society itself can be a tyrant, operating collectively over the individuals that compose it and potentially reaching a level of oppression where the tyranny of the prevailing opinion penetrates deeply into the details of life and enslaves the individuals’ soul itself. Yes, for Mill, the tyranny of the majority can enslave the individuals’ soul; therefore, he concludes that a limit to the legitimate interference of society must be imposed.

And for Mill, there are two ways in which society can restrain the actions of the individual and impose a rule of conduct: by law and by opinion. Not only can legal penalties control the individual, but there is also a practical guiding morality rising from the customs, cultural standards and other individuals’ opinions that can act as moral coercion.

The harm principle

To find where the limit of the government authority lies, regardless of how it is enforced, Mill defines the harm principle with the prescription that if you follow this principle, you will find where to place this limit. The principle is as clearly stated as its declension is still open for debate today.

A full extract from the essay reads as follows. “The principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

In other words, society can interject on a person’s liberty only to prevent harm from being caused to others. Sometimes, this states: “your freedom to swing your punch stops where my nose starts.”

Mill recognises one exception: this principle applies only to those in the maturity of their faculty. Children and “young persons below the age”, “who are still in a state to require being taken care of by others”, Mill writes, “must be protected against their own actions as well as against external injuries.”

The drunk man example

In the essay, Mill applies the harm principle to the case of the drunk. For Mill, there are two types of drunk behaviours: illegitimate and idle. Illegitimate behaviours are those behaviours that cause direct harm to others, like violent acts performed under the influence of alcohol. Mill is crystal clear on this point, the abuse of alcohol that excites a person to the point of harming others is criminal, i.e. must be stopped by law. On the other hand, another abuse of alcohol, which just renders the drunk idle, inoffensive towards others, is not to be considered criminal. The idle drunk actions are to be considered harmful only towards himself, not harmful towards others, and therefore are not to be interfered with by society. An inoffensive-towards-others drunk is, for Mill, within the expression of his rightful liberty and only tyranny could make him the subject of legal punishment or moral coercion.

The drunk man burden I am now going to depart from Mill and do two things: build a little bit on top of his ideas, expand on them if you will, and then I will connect them with the current world situation. You will see that the extension is quite natural and straightforward, but for clarity, I am pointing out that what follows is not part of Mill’s essay.

Mill doesn’t touch on in his essay the potential burden on society of the drunk. The criminal drunk burdens the legal and juridical system — as every criminal act does, this should be of no surprise — and also the idle drunk brings a potential burden on society. For instance, the idle drunk could become a burden the moment he hurts himself to the point where he has to check into the hospital and require a level of medical assistance, the cost of which could be in one way or another shared with others in the community.

I contend that Mill doesn’t touch on this point because a burden on society of an individual is always expected to some degree. This is one of the purposes of society: to collectively support each other as it is more advantageous than being alone. And although it can be a reasonable reaction for some members of society to look ill towards those who they perceive to take more than they contribute, burdening others is not the same as harming others. Mill, who is a utilitarian, maintains that the liberty of the idle drunk has to be protected, implicitly arguing that the potential burden on society is not to be weighed against the burden on society of interfering with his actions.

In other words, Mill does not build an argument based on burden efficiency. I contend that Mill accepts that a society that abides by the harm principle as a limiter between govern authorship and individual liberty is a society that does not minimise the burden of each individual on society. Such minimisation of burden would instead belong to a tyrannical society.

Similarly to what Mill does in his introduction, confirmation can be found in history. For example, it was allowed in ancient Rome for one man to relieve the senate and become dictator for a short time. This was allowed in times of war, where a military emergency warranted efficiency over freedom to guarantee the survival of the society; in case of emergency, excessive powers were granted. Incidentally, this mechanism that was meant as a safeguard was abused by a general and politician named Gaius Julius Caesar, who did not surrender his dictatorship power back to the Senate, leading to the eventual demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. At times, History poetically reveals itself.

Many drunk men can break a healthcare system

So now we can finally connect Mill’s drunk example to the current situation, which would be equivalent to having so many idle drunk men that if even just a fraction of them would harm themselves to the point of going to the hospital in need of a liver treatment it would burden the healthcare system, rendering it unusable for everyone else and the entirety of society.

It is the magnitude of the threat that brings society to react in self-preservation by declaring an emergency, transitioning from a government of the harm principle to a temporary dictatorship — a tyranny of the masses, to borrow terminology from Mill. I argue that this is the situation in which we found ourselves today.

We are not facing a society that is interfering with the idle drunk because of his threat to harm others. The current political reach into the citizens’ lives is not a consequence of an application of the harm principle, but a reaction aimed at self-preservation. In support of this argument are the governments’ declarations of national emergency, which were done to allow the governments to enact extraordinary measures in response to a grave threat.

The current extraordinary policies are motivated by self-preservation against an escalated risk of the burden on society. It is not a higher risk of harm to others that triggered the emergency response of society, it is not the risk of harm caused by the transmission of the Sars-Covid-2 virus, but it is instead the escalation of risk to levels dangerous for the survival of society itself.

In the current situation, the risk is not any more the risk towards others, but the risk towards so many others that this many others can be considered the totality of society itself.

This distinction, albeit fine, is extremely important for two reasons. First, because it provides the proper context for further reasoning. For example, we could be asking if the current response is warranted or not. If it was at the beginning? If it is still now? And if yes, then when will it cease to be? An analysis of these questions is beyond the scope of what is treated here, and their answer irrelevant for the argument brought forward so far, but a proper frame for questioning is always an indispensable tool in achieving further reliable answers in the future.

Second, because it is by remembering that we are in a tyrannous emergency that exceeds what it would normally be allowed, that a claim back to order will be advocated once the emergency will be over. It will be imperative to restore a healthy balance between the individual’s liberties and the government authority. Perhaps the strength of our society will be tested and we will see if we will be able to come back to our most valuable rights.

Comments powered by Disqus.